Behind the Screens: Museums, Social Media, and Creating Educational Entertainment

Guest post by Kaitlin Janecke

As a 2015 twenty-something, my day typically starts off with screens. Within five minutes of waking up, I’m probably connected to the internet. I’m not really proud of it, but I’m not alone. Like so many others of my generation, I have emails that need checking, my calendar needs confirmations, and if I’m lucky, my updates will show a new article on the University of Michigan Herbarium macrofungi collection.

Think that last statement is a stretch? I’m among the hundreds of people who received that article in their Facebook feeds, and the millions who love to learn about museum collections through social media. It’s hard to imagine the technology-loving lifestyle of today’s developed world as anything but at odds with natural history museums, filled with quiet halls and remnants of past ages. With flashing screens and constantly updating content, it might be a reflex to say that technology, especially social media, is creating a generation of short-attention spans and disdain for anything without a Wi-Fi connection. Admittedly, some of this might be true. Attendance at museums worldwide has been chronically low for the last decade, and many institutions have faced financial issues. However, social media is proving itself to be a strong force for creating a wider interest in museums with positive web presences. Embracing the use of trending tags and specimen selfies may be just what museums need to connect a global audience with natural history collections.

Janecke poses for a specimen selfie with a young Tundra Swan (Cygnus columbianus). (Photo by Kaitlin Janecke)

Museums need fresh visitors, and this usually means new exhibits and advertising to the public. Traditionally, this has meant brochures, flyers, radio and television spots, and more recently, an update to the museum’s website. Most of these only reach people on a local scale, and only occasionally regionally. Yes, these are the people who are most likely to visit, and entrance fees keep museums running. However, this isn’t going to cut it in today’s global community. In the Google age, it’s hard to place value on things that cannot be seen by the masses, and not just those within a hundred miles. New exhibits, while extraordinary in person, have a harder time gaining relevance to the more distant public. If we cannot bring everyone to our particular institutions, and we want museums to stay valued, we must bring the collections to the people.

Most museums have websites and Facebook pages by now, which can help to spread the word about museum events, new additions, and articles written about collections materials. These are great places to start, but what really draws in viewers is a direct connection with someone who cares about a museum and the collections it holds, and who can show off how interesting and relevant it is through great communication skills. The most famous of these communicators is Emily Graslie, host of The Brain Scoop. Graslie began as a volunteer at the Philip L. Wright Zoological Museum, and started an exploratory YouTube channel with the help of vlogger/”internet guy” Hank Green. The Brain Scoop videos cover museum specimens, preparing new skins, and the ecology and biology of different animals found in the collections. Graslie has since moved to a permanent position at The Field Museum and continues The Brain Scoop as the Field’s Chief Curiosity Correspondent. This has greatly increased the visibility of the Field’s collections, with almost 300 thousand YouTube users subscribed to The Brain Scoop channel and over 11 million combined views in less than three years. Having talked with many fans of the channel, and being one myself, I can say that Graslie’s genuine love for learning and interest in museum collections have inspired many to travel further than they might have normally, just to visit the Field Museum. Fans of The Brain Scoop also recently donated over 150 thousand dollars to build a new striped hyena diorama in The Field Museum’s Hall of Asian Mammals. YouTube may not have been where the Field expected to find a new and dedicated group of young museum patrons, but the donations and the thousands of video comments from people hoping to go to the Field speak for themselves.

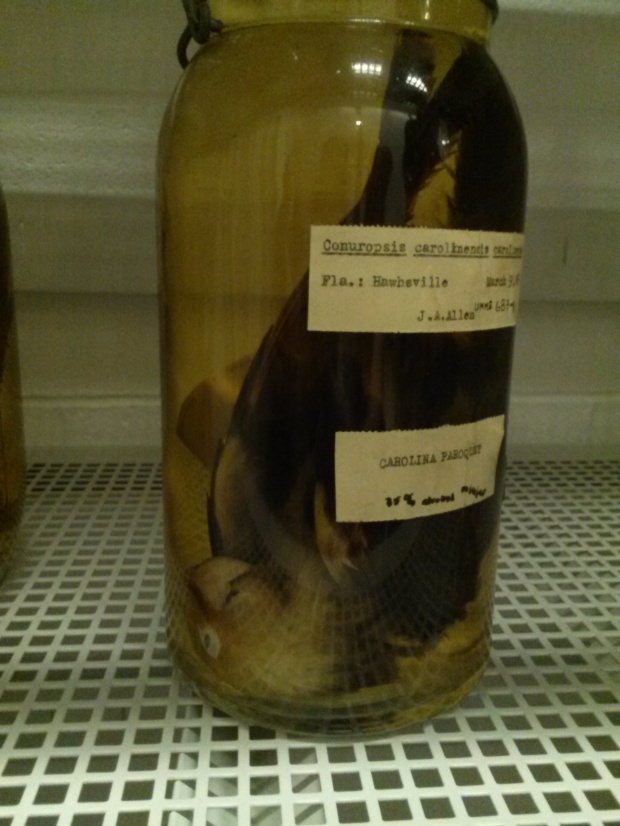

To the untrained eye, this might just be a jarred bird. A proper communicator could turn this photograph into an educational moment about the extinction of the Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis), as well as a great Instagram post that could reach millions. (Photo by Kaitlin Janecke)

Admittedly, the popularity of The Brain Scoop is a bit of an outlier. The Field Museum has provided Graslie with a paid job, great resources, and access to the researchers working out of its collection. Still, the channel’s success shows us what can be done when collections are shown to the world as incredible sources of both knowledge and inspiration, and museum-enthusiasts everywhere are stepping up to bring phenomenal collections to a screen near you. Educational filmmaker Charlie Engelman created a fabulous Insect Week series with the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology (UMMZ) Insect Division, in which he talked with collection manager Mark O’Brien about fascinating species and groups of insects, their adaptations, and about the care and storage of a museum collection. If you’re looking for strictly visual material, a growing number of Tumblr blogs are being created by museum staff members and volunteers. The Royal Ontario Museum has a great blog about its children’s programming, including drawings of specimens, photographs from camps, and posts by teens exploring the museum. For more informal work, I suggest Things on my Desk for The Field Museum and So Much Science for The Slater Museum. These are projects being created out of love, but what could be done with more resources?

Outside the University of Michigan Alexander G. Ruthven Museums Building. (Photo by Kaitlin Janecke)

When I started my own Tumblr blog, Life with Dead Birds, about my work as a research assistant in the UMMZ Bird Division, I mainly wanted to practice my communications skills. I’ve been extremely fortunate with the amount of publicity my work has been getting around the both the university and museum communities over the last months, and I now entertain a classroom of over 250 virtual individuals. I’m incredibly happy knowing that I’ve helped to keep people interested in museum collections, but running even my small blog isn’t easy. My posts are relatively short, maybe only a paragraph or two, but they still take about an hour to research and write. I take time out of my day to photograph specimens and ask questions of other people in the research hall, and I’ve found myself debating whether I can afford a better camera. I’ve recently graduated, and now that I’m not working for the UMMZ, I’m worried about my posting schedule, how I should adjust my materials, and creating better lesson plans to draw a larger audience. Frankly, this is a lot of time and effort for a side project when I’m searching for a full-time job. I can’t imagine trying to create more time-consuming media, like videos or full lesson plans, in my current situation. I want to give my audience my best, but as long as I’m doing this as a project and not a career, I can only give so much.

Many species of bird come in dabbled browns, tans, and whites. Having readers guess the species from a photo gives beginners an opportunity to look at field guides, identification websites, and other resources, while letting seasoned pros practice their skills from memory. Can you identify this bird? (Photo by Kaitlin Janecke)

Museums need more visibility, especially in their collections. A growing cohort of content creators can provide that visibility, but many of us are doing this on our own time and budget. If museums want to get serious about staying in the public eye, they need to hire some of the vastly talented writers, filmmakers, and outright curious people chomping at the bit to help them. We need more Curiosity Correspondents, armed with cameras and a Wi-Fi signal, who can demystify what goes on in the back rooms of research halls, while showing off the beauty and fun of science itself. Museums can finally show off all of the amazing specimens that have been hiding in drawers and cabinets for decades; they just need to fund a more modern team of educators, advertisers, and spokespeople.

It’s a fast-paced world, and it can be hard for places like natural history museums, which revel in how slow processes bring big changes, to stay relevant. However, by combining the instant connections of the digital age with the joy of learning about the amazing planet we inhabit, we might just redefine our own history.

Opening a museum collections drawer offers endless opportunity for educational web content. These drawers of swallows (family Hirundinidae) could be used to teach about aerial hunting strategies, the use of human structures as nest sites, or how wing shape relates to flight style, all without having to remove them from the collection. (Photo by Kaitlin Janecke)

Kaitlin Janecke is the creator of Life with Dead Birds, a museum collection blog based in the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology (UMMZ), where she worked in the Bird Division while completing her B.S. in ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Michigan. She has held various positions in science communication for the last seven years and has also been a researcher, wildlife rehabilitator, and volunteer events coordinator. She now works as an educator at the Kalamazoo Nature Center and continues to post about the UMMZ bird specimens at lifewithdeadbirds.tumblr.com.

Next time on Cracking the Collections:

October 10 – Colleen Evans shares her experiences managing natural history collections, including the U.S. National Tick Collection, for Georgia Southern University in an Old Collections with New Managers post.

Do millennials not wear gloves when handling specimens? 🙂

Actually, we have a very specific policy on gloves in the UMMZ Bird Division. Our collection manager has found that gloves can actually cause more harm than good to our specimens. Gloves can snag on feet, stick to feathers, and actually pull out loose parts of a skin. On top of this, gloves can really dull the tactile sense of a handler, and we want to avoid dropping or harming specimens because we can’t feel the specimen properly. Unless a specimen is obviously in an especially fragile condition, we do not want to risk injury through gloves. Instead, to keep the specimens clean, we make sure that anyone handling specimens washes their hands before and after handling specimens, and that they use good judgment in handling older specimens.

Pingback: Best Reads, Listens & Views of 2015 » Biodiversity in Focus Blog

Pingback: It’s Our Two Year Anniversary! | Cracking the Collections